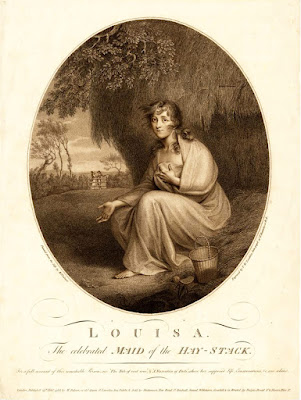

Whilst researching my PhD, I stumbled upon a sweet but sad little story set in Somerset. An apparent true story, it was reported in The Lady’s Monthly Museum in 1801 that a "madwoman" had appeared in the Bristol region living ‘under a haystack’ and could not be coaxed to reside in a house until a lady persuaded her to go to an unnamed local private asylum nearby.[2] The location, ‘four miles from Bristol’ and the date given of admission, 1781, means it was probably Fishponds Asylum, Somerset - a well-known and renowned asylum which was opened in 1740.[3] When she was released "Louisa" returned to sleeping in the haystack and refused to move. Finally, she was apprehended and was admitted to "Guy’s Lunatic Hospital" in Bristol.[4] Louisa was described as ‘beautiful, graceful and elegant’, with the ‘deportment and conversation of superior breeding’.[6] A portrait of "Louisa" is shown below.

In 1804, this story was republished anonymously as a chapbook in London. This type of gothic chapbook, described sometimes as a ‘Shilling Shocker’, was a cheaply printed short – sometimes serialised – book aimed at the general public , much like a "Penny Dreadful" would become in later years.[7] The Chapbook had this fantastic title:

The Affecting History of Louisa, the Wandering Maniac, or,

‘Lady of the Hay-Stack;’ So called, from having taken up her Residence under

that Shelter, in the Village of Bourton, Near Bristol, in a State of Melancholy

Derangement: A Real Tale of Woe.

Despite that it is difficult to find any mention of Louisa in the papers, another character from this little drama was indeed a real person! Hannah Moore, who is said to have paid for the girl's charity was in fact a poet and a vocal supporter of the abolition of slavery. Hannah was deeply enriched in Christian values and abhorred seeing people in states of great poverty. Due to this, she set up a series of charitable institutions and schools for impoverished girls in Somerset.

|

| Hannah Moore - Louisa's benefactor |

Another poet, Ann Yearsy of Bristol even wrote a poem about Louisa -

Despite knowing quite a bit about Louisa's life after she was found from the accounts of poets and also the doctor who treated her until her death in Guy's hospital in 1801, one thing has never been discovered - who really was Louisa? I guess only conjecture remains!

[1] ‘Louisa, The Lady of the Haystack’, p.420.

[2] ‘Louisa, The Lady of the Haystack’, p.422.

[3] In 1781, the only private asylums which operated in the region were Fishponds and Nailsea. Fishponds was located three miles from Bristol, whilst Nailsea was eleven miles.

[4] This was the asylum which was attached to the workhouse.

[5] ‘Louisa, The Lady of the Haystack’, p.423.

[6] ‘Louisa, The Lady of the Haystack’, p.421.

[7] Franz Potter, Gothic Chapbooks, Bluebooks and Shilling Shockers, (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2021), p.41.

[8] James Boeden,. The Maid of Bristol: A Play in Three Acts. (New York: D. Longworth, 1803).

[9] Anon, Louisa, Lady of the Haystack, p.7.