Now that I am done with the PhD, I can finally share some of the discoveries I made whilst completing it! One of the very first things I did, back when I started was to map out the locations of private mental health establishments from 1750 - 1860. (Any info in this blog post can be further explored by reading my thesis which will be available online from 11/4/25 or cited as "Emma Barrett, A Delicate Matter: the private asylums of the South West of England 1770 - 1851, PhD Thesis, University of Plymouth, 2024.")

First, let me briefly explain what a private asylum was!

So, back in the 1700s, the care of the mentally unwell fell to what was called "The Parish" - think like a local council. This was later changed to unions but still run locally. Hospitals for the mentally unwell as we think of them now just didn't exist because people were only just starting to realise that mental illness was an illness at all! There was of course the infamous Bethlem in London and other charitable institutions but most likely if you were poor and mentally unwell you were bound for the nearest workhouse. The rich and unwell were predominantly cared for at home.

In the mid 1700s a new "craze" began, as businessmen, clergy, and doctors too began to realise there was the potential to make money by housing the mentally unwell (and later treating them) in privately run "lunatic asylums" - also known as madhouses. These started out as almost like care homes for the rich mentally unwell, but were soon taking on poorer patients too, paid for by the parish unions. Before 1770 this was completely ungoverned! No lists of patients, licencing or records had to be kept at all and anybody could set up shop as a madhouse. In 1770, a bill passed into law that any houses such as these had to at least be licenced and had to keep a register of who they housed. This suddenly became a booming business - especially in the south west of England but all over the country too!

However, madhouses soon picked up a bad reputation!

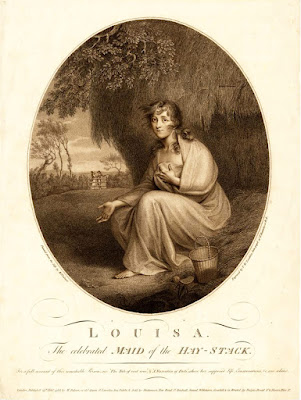

Stories became rife of mistreatment, unnecessary detainment and people being forced into asylums in order to steal fortunes. Women, it was told, were especially vulnerable to being locked away by unscrupulous husbands and fathers. Now, this reputation doesn't entirely hold up when these asylums are studied, and my thesis goes further into how this damning reputation was created, however for this post all we need to say is that there was a real mixture of different types of asylums, all with different conditions within (from the very good, to very poor). There was not, however, the abundance of forcibly held sane people that literature and public opinion would have you believe.

In the south west, there were more private asylums than anywhere else in the country - three times as many at one point! I will attach a map I created for my thesis to demonstrate the sheer numbers here - it's a little hard to read on this scale but at least shows you the numbers and rough locations:

Additionally,

Edward Long Fox Physician Cleave

hill, Brislington

William Finch (2) Physician Laverstock

Charles Langworthy Physician Kingsdown

Robert Langworthy Physician Longwood,

Kingsdown

William Finch (1) Not Medical Laverstock

Ann Hinks Not

Medical Nailsea

Martha Hinks Not

Medical Nailsea

Justinian Mercer Not Medical Halstock

Caroline Finch Not

Medical Laverstock

William Gillett Not

Medical Fivehead

Robert Willett Not

Medical Market Lavington

Zachariah Jefferies Physic Kingsdown

Nehemiah Duck Surgeon Cleve,

Ridgeway

James Rich Surgeon Ford House

Richard Langworthy Surgeon Plympton

john J Mercer Surgeon

and Apoc Halstock

William Spicer Not

Medical Broadhayes

William Symes Surgeon Cranbourne

William E Gillet Surgeon

and Apoc Fivehead, Fairwater

James Duck Physician Cleve, Fullands, Plympton

Charls Finch Not

Medical Fisherton (plus others)

Joseph Spry Not

Medical Bailbrook

Elizabeth Langworthy Not Medical Kingsdown

Joseph F Spencer Surgeon Fonthill

William C Finch Surgeon Fisherton

(plus others not in region)

Betsey Mercer Not

Medical Halstock

Alice Mercer Not

Medical Halstock

For anybody who is interested, I do have a future post planned which will explain the different job titles the medical professionals had - when it's done I will add a link here :)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)